May 7, 2021

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, many families decided not to enroll their children in preschool or kindergarten this school year. This raises two key questions as we look ahead to Fall 2021: (a) Will the children who arrive for preschool, kindergarten, and even grade 1 be prepared for the social, emotional, and academic demands of in-person learning? (b) What can educators and families do now to support children’s success?

We recently discussed these questions with Dr. Jan Bryan, Vice President and National Education Officer, and Dr. Scott McConnell, Director of Assessment Innovation. We were joined by two of our colleagues who are also the parents of preschool children: Ali Good, Senior Director of Product Marketing, and Heidi Lund, Product Manager.

Why have the COVID-19 disruptions affected early learners so significantly?

Scott McConnell: So much of what we do in preschool and kindergarten is hands-on. That’s why we tend to structure these classrooms around “activity centers” where kids are interacting with each other and with physical objects—such as blocks and tiles—to get an understanding of how the world works. Activity centers are also the place where teachers “drop in” to comment, reinforce, and expand on young learners’ actions. This mix of child-child, child-teacher, and physical interaction is difficult to reproduce in a remote learning environment.

For many children, preschool or kindergarten is also the first time they’re left in the care of an adult who isn’t a family member for an extended time period. We hear a lot about “shyness” at the beginning of the school year, as children figure out how they’re going to interact with this new adult, what they’re going to do when they’re asked to line up, wait for their turn, etc. This is another important learning experience that’s difficult to reproduce virtually.

Compare this to the experience of a high school student who’s enrolled in, say, pre-calculus. Granted, many teenagers aren’t enthusiastic about advanced math classes. But when school buildings are closed, lessons can be delivered over Zoom, and these older students are much more capable of reading the textbook and working through problems on their own. Over their years of schooling, they’ve learned to self-regulate and to manage their learning in ways that younger children cannot.

Jan Bryan: I know a family with a 3-year-old and a 9-year-old, both of whom are learning at home this year. The 9-year-old is doing well with online learning. Once the school day ends, she often logs back in to chat with her friends, just as she used to do in the lunchroom or during recess.

The 3-year-old obviously doesn’t have this option. He’s doing well academically—either his parents or his grandparents talk and read to him during the day, and he practices saying the letters and numbers, so he’s having a lot of the same educational experiences he would have had in preschool. What’s missing is the opportunity to interact with other 3-year-olds. The writer Dylan Wiliam says that a child’s best resource is another child, and I suspect that every early childhood educator can think of a student who arrived at school not wanting to share or take turns—and who faced the natural consequences of this from his or her peers.

As Scott said, this peer-to-peer interaction is a critical social-emotional learning experience that may have been missed this year. The 3-year-old communicates beautifully with his parents, but they have no way of knowing whether he can communicate with other 3-year-olds.

Why will kindergarten readiness present such unique challenges this fall?

Ali Good: My son turned 5 a few weeks ago, so I can share firsthand experience here. He attends Montessori school now, so we have to decide whether to enroll him in public school for kindergarten or to continue in Montessori for another year, since it offers a kindergarten curriculum.

The pandemic made the decision a lot more difficult. I wasn’t able to visit schools or meet with staff. They did offer Zoom meetings where the principal and several teachers answered questions—but it’s difficult to get a sense of the spirit of a school and of the educators who teach there via Zoom. A lot of my information came from connecting with other parents, especially through social media groups.

What makes Fall 2021 unique is also the number of children who—because of COVID-19—are not enrolled in either preschool or kindergarten this year. What will their families decide to do in the fall? Will we suddenly have a large number of 6-year-olds enrolled in kindergarten? Or will these students go directly to first grade, skipping kindergarten completely?

Each scenario presents challenges, especially in terms of staffing and resource allocation. During the Zoom calls, I asked principals what they were expecting in terms of kindergarten and first-grade enrollment in the fall. The consistent response was, “We’re not sure.”

Scott McConnell: Different US states have different “cut-off” dates for kindergarten eligibility. Every year, you’ll have kids who turn 5 on the first day of eligibility and kids who turn 5 on the last day of eligibility entering kindergarten and learning together. So, you could have kids who are 5 years and 1 day old and kids who are 6 years old in the same program. That’s a difference of almost 20 percent of their lives. As a result, some children will have had significantly more time than others to learn language, to learn about the world, and to learn about themselves—and to learn how to use this knowledge and how to gather more of it.

Kids also bring a wide variety of experiences to kindergarten. Some will be from two-parent homes and others from single-parent homes. Some will be native English speakers while others will be recent immigrants. Some will be reading semi-independently while others are just learning the alphabet. My point is that every year, kindergarten educators have an incredible mix of children and skills in the same classroom—but they can use both previous experience and their knowledge of the community to draw some general conclusions: X percent of students speak English at home, Y percent qualify for free or reduced lunch, etc.

In Fall 2021, however, I don’t think educators will feel confident making predictions like this. In addition to children “red-shirting” this year, we’ll have families who’ve had to move to a different city or state due to the loss of employment, along with children who’ve had to move in with grandparents or other family members because of the pandemic. I think educators’ first question this fall will be: Who are these children? And what are their immediate needs?

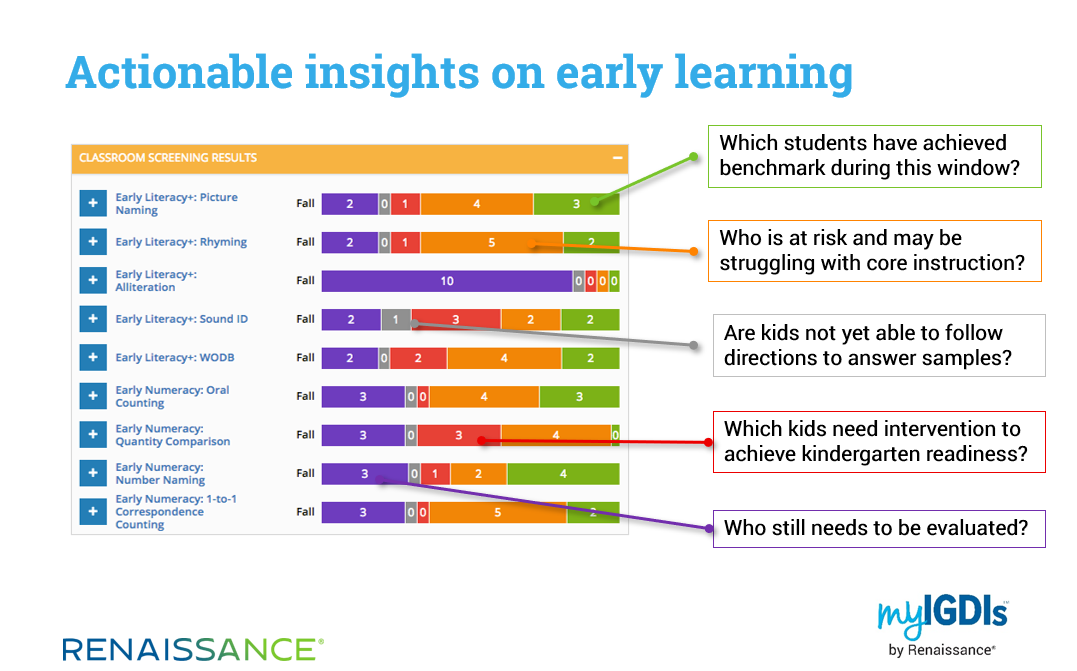

This is why formal assessment and teacher observations will be so critical, because we’ll be starting with much more of a “blank slate” than usual. There’s sometimes a reluctance to assess kindergarten students early in the school year, on the grounds that they need 6–8 weeks to acclimate to the classroom, to get used to their teacher, etc. In Fall 2021, I think this would be 6–8 weeks that educators are wasting. Because of the disruption to schooling this year, we’ll really need to press on the accelerator.

Luckily, we have an increasing number of assessment tools that kindergarteners find engaging—so there will be less need to wait.

What advice do you have for teachers and administrators as they look ahead to fall?

Heidi Lund: Even before COVID-19, kindergarten placement could be a difficult conversation. As Scott pointed out, you’ll always have children whose birthdays are either right before or right after the cut-off date. My older son was born in January, so he was already 5-and-a-half when he started kindergarten. My younger son was born in June, however. He’s 3 and in preschool now, but my husband and I are already discussing whether to send him to kindergarten at age 5 or to wait until he’s 6.

My plan is to be strategic, but to also take a “wait-and-see” approach. I’ll register him to enter kindergarten at age 5, so I’m not scrambling to enroll him at the last minute. When he turns 5, I’ll see what his knowledge is like, what his demeanor is like, how his social skills are—and I’ll have a backup plan in place if we then decide to wait another year. I’ll also be assessing him for kindergarten readiness. While test scores won’t be the only factor I consider, they’ll go a long way toward validating what I already suspect and will provide additional data points for consideration.

At Renaissance, we offer myIGDIs for Preschool to assess children’s kindergarten readiness and ongoing development. myIGDIs provides early literacy measures in English and Spanish, along with early numeracy measures and observational assessments of children’s social-emotional and related development. Measures can be administered either in-person or remotely, and the easy-to-read reporting shows how children are performing in relation to seasonal benchmarks.

In addition to myIGDIs, we offer Star CBM and Star Early Literacy for assessing students in K–1 (and beyond), and we recently added a popular foundational literacy program called Lalilo to the Renaissance family. So, in response to the uncertainty caused by the pandemic, I’d remind educators that they have access to tools and resources that help to answer key questions about their students, to identify students’ individual needs, and to validate the knowns and unknowns about students’ proficiency.

These data points will also be critical for administrators, as they work to ensure that classrooms are resourced appropriately. For example, next year’s kindergarteners probably won’t need instruction on how to use a touchscreen—they’ve had plenty of experience this year! But in other areas, children’s instructional needs will likely be greater than in the past, especially if they’ve missed out on peer-to-peer interaction. Gathering as much observational data as possible this spring and summer, and then assessing children when the new school year begins, will help administrators to budget for and provide the right programming and resources to these children.

Jan Bryan: That’s such an important point, Heidi. Most teachers and administrators have seen enough and have enough life experience that when they meet these children, they’ll begin to form an understanding of their needs pretty quickly—I’ve seen this before, I’ve walked this path before with a child. As you noted, one important role of assessment is to validate what educators already feel instinctively.

But assessment is also critical for identifying needs that we might otherwise miss. I’ve seen the term “leapfrogging” used to describe this, in the sense that if we don’t assess, we’re in danger of moving ahead too quickly and skipping important skills that a child hasn’t learned yet. Given everything we’ve said today, it’s clear that educators will need to make full use of both aspects of assessment next fall—combining their observations and instincts with specific data points provided by their assessment tools. When you put the two pieces together, you really start to see the pathway ahead for each child.

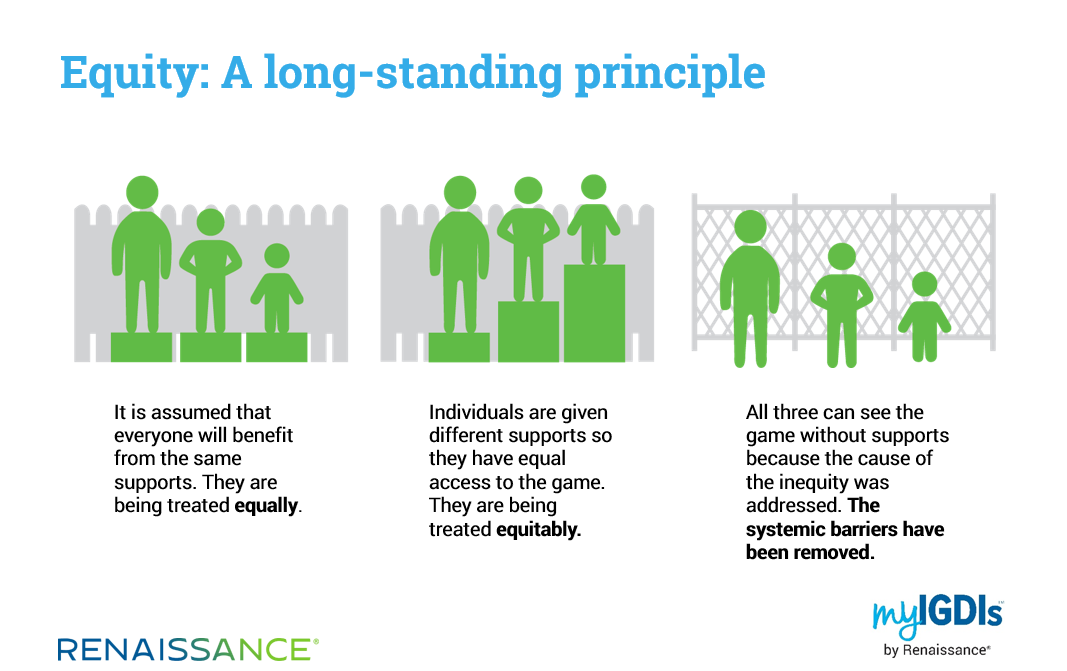

Scott McConnell: For better or worse, US education has traditionally taken a “cookie-cutter” approach, where all first graders learn addition, all second graders learn subtraction, and so on. We’ve known for a long time that this approach works for some students but not for others. We’ve also known for years that if you give every student the same thing, you won’t get the same results. Educational equity depends not on “sameness” but on allocating support differentially, so we give more to the kids who need more. This has been a long-standing practice in education, even before it was formalized in special education programs and Response to Intervention (RTI) models.

Over the last several years, we’ve seen a move away from the cookie-cutter approach toward something we refer to as continuous learning. Simply put, this means that educators use technology to do what it does best—to support targeted and personalized learning experiences, whether children are in the school building or not. I think the pandemic will only accelerate this shift. In the fall, it won’t be a matter of doing new things but of doing more of the things we know are effective. We’ll need to be more attentive to the different needs of children in the same classroom, and we’ll likely need to be more flexible in grouping students and reallocating resources to where they’re needed the most.

Administrators will also need to be prepared with on-the-fly professional development for their teachers. Because of the disruptions, many more children will arrive in kindergarten and first grade missing foundational skills they would otherwise have developed. For teachers, it won’t be a matter of reviewing these skills with children but rather of starting from scratch. And this is where assessment data will help the most—showing us what kids need right now, and then helping us to track their progress throughout the year.

Looking for reliable data on your early learners’ strengths and instructional needs? See how the following Renaissance products will help to guide your decision-making throughout the school year:

- myIGDIs for Preschool (assessment)

- Star CBM (assessment)

- Star Early Literacy (assessment)

- Lalilo (foundational reading skill development)

Also, check out Scott and Jan’s webinar for more helpful insights on guiding students’ early learning journeys.