September 26, 2019

Every minute of every day, students all over the world learn to read in their first language. And millions of students go through this process in a second language as well. For many of these students, the additional language of choice is English. According to research from the British Council, over one billion people are currently learning English worldwide, and this is expected to double in a little over five years.

Essential to the development of high levels of proficiency in any language is the ability to comprehend texts written and read by native speakers of the language. Despite years of study, however, most students will struggle to achieve this level of literacy in English—the level necessary for opportunities in their future academic and professional careers. According to English First, an organization that has tested and ranked English proficiency around the world for seven years in a row, English Learners in 45 of the 80 countries tested in 2016 failed to demonstrate even moderate English language proficiency. This means that more than half of today’s students learning English as an additional, foreign, or second language are not likely to develop enough proficiency to reap the benefits as adults.

The challenge for English Learners is twofold. First, they are often provided with simplified reading materials that are not generally used in native English-speaking classrooms. Lacking exposure to the complex texts read by native speakers, these students will forever struggle to compete. Simply providing English Learners with access to authentic texts, however, is not enough. Students must understand the texts they are provided. Without comprehension, there are no gains. How, then, do we (1) provide English Learners with access to authentic English-language texts, and (2) facilitate comprehension of those texts?

This post answers these questions by providing context, reviewing research, and suggesting a solution for improving English Learners’ literacy.

Factors affecting English Learners’ literacy achievement

According to the International Literacy Association, “literacy is the ability to identify, understand, interpret, create, compute, and communicate using visual, audible, and digital materials across disciplines and in any context.” Implied without being stated directly in this definition is an important factor that affects reading ability: the reader’s level of language proficiency.

Essential to the improvement of English Learners’ literacy skills is an understanding of (1) the basic components of language, and (2) the relationship between the four language domains (listening, speaking, reading, and writing). Let’s begin with the basic language components—sounds, words, and grammar—and consider how each affects literacy.

Basic language components

Sounds. Every language uses different sounds. Consider vowel sounds. Native speakers of all languages use their vowel sounds when listening, speaking, sounding out words when reading, and spelling words when writing. Think about native Spanish speakers learning English. Spanish has five vowel sounds, while American English has 14 or 15, depending on the dialect. Native speakers of Spanish will easily hear the difference between the English words “boot” and “boat,” because both vowel sounds exist in Spanish. They will likely struggle, however, to hear the difference between “bet,” “bit,” “but,” “bout,” and “bought,” because these vowel sounds do not exist in Spanish. These differences affect comprehension when decoding. Why this matters: The more fully a student acquires the sound system of English, the more easily she or he can decode and determine meaning when reading.

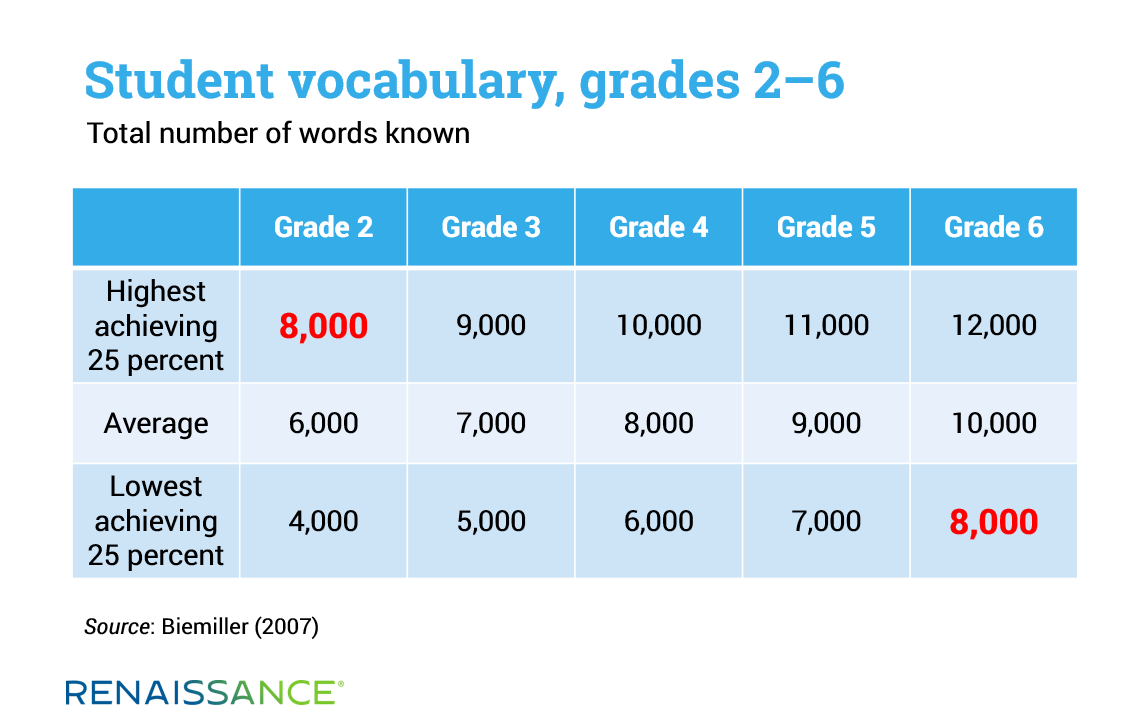

Words. Providing English Learners with texts written and read by native speakers requires knowledge of how many words a native speaker of English generally holds in his or her lexicon. Research by Andy Biemiller (2007) reveals that the highest achieving 25 percent of native English speakers know approximately 8,000 root words by grade 2 (age 7), while those at the lowest 25 percent only know 4,000 words. Further research on grades 3–6 (ages 8–11) reveals that the highest achieving 25 percent of students in grade 6 have added an additional 4,000 words to their vocabulary. Perhaps most shocking is that the lowest achieving 25 percent of grade 6 students only know 8,000 words—the number typical of high achieving grade 2 students. Why this matters: Simply stated, the number of words students know determines what they comprehend when they’re reading. More is definitely better.

Grammar. Older students learning English are generally very knowledgeable about grammar. For example, they can easily identify the “third person singular masculine subject pronoun” as “he”—something a native speaker cannot always do. However, a native speaker intuitively understands the difference in meaning between “he’s riding a bike” and “he rides a bike” when reading a passage. Why this matters: Grammatical structure affects meaning. Using grammar matters; explaining rules does not.

Now that we’ve seen how the basic components of language acquisition affect literacy, let’s look at the relationship between language skills and the development of literacy.

Language domains

Taking advantage of the relationship between listening and reading is another way to improve English Learners’ literacy skills. According to reading expert Jim Trelease (2013), listening vocabulary becomes speaking vocabulary, which then becomes reading vocabulary and, finally, writing vocabulary. This means that once students know how to decode English, gains in their listening vocabulary support gains in reading comprehension whenever they encounter the newly learned words in a text.

Gains in the sound system, vocabulary, and grammatical structure support gains in listening comprehension. Collectively, these gains lead to higher levels of reading achievement. It may appear, then, that increased access to listening materials is the answer. The reality is that not all listening opportunities are created equal. Increasing a student’s foundational listening ability requires input that is ”comprehensible.” As with reading comprehension, listening comprehension must be at the right level for the individual. If what students hear is either too basic or too complex, no gains occur.

Making input comprehensible for English Learners

According to researchers Stephen Krashen (1985) and Bill VanPatten (2014), to develop language, learners must hear and see language as it is used to express meaning. There are no shortcuts. Input itself does not guarantee acquisition, however. Nothing does. But acquisition cannot happen in the absence of input. Why this matters: Acquisition develops with comprehensible input.

Listening and reading are receptive skills; both are forms of language input. Improving literacy requires: (1) making both listening and reading comprehensible to the individual student, and (2) understanding that gains in listening support gains in reading. Why comprehensible input is essential is clear. How to make input comprehensible is the next question we’ll consider.

The critical role of vocabulary coverage

Knowing how many words a student knows (vocabulary knowledge) does not address the issue of how many words in a text a reader needs to already know in order to understand it (vocabulary coverage). Research on vocabulary coverage has been prevalent for the past 25 years, particularly in countries with large numbers of students learning English as an additional language. The overall conclusion of these studies is that readers must already know 90–100 percent of the words in any text in order to comprehend it.

Schmitt, Jiang, & Grabe (2011) put this conclusion to the test. Participants in their study already knew 90–100 percent of the words in the passage they were asked to read. Yet text comprehension ranged from just 50 percent for students with 90 percent word coverage, to around 80 percent for students who already knew every word in the text.

As this research shows, knowing every word in a text is not enough to fully understand it. This leads to the second factor that affects reading comprehension: background knowledge. Although the following research is not recent, both studies provide strong evidence of the critical role of background knowledge on reading comprehension.

The critical role of background knowledge

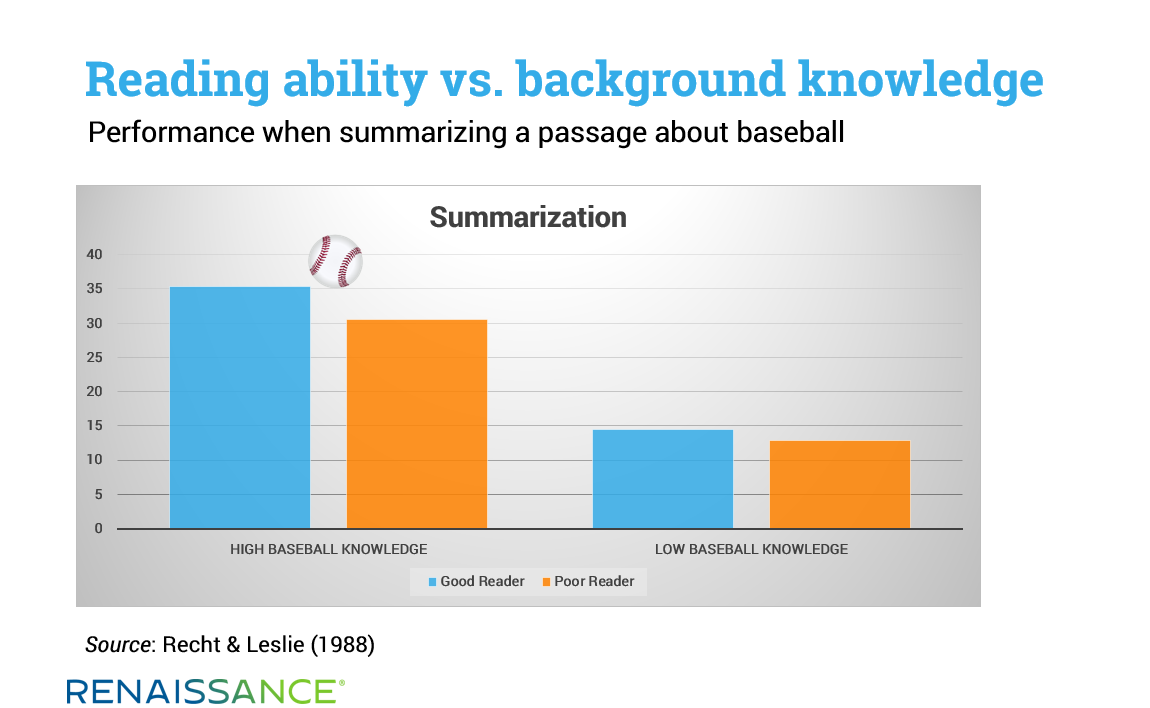

In 1988, Recht & Leslie conducted a study on background knowledge, examining how input affects output. Participants in the study were divided into four groups:

- Good readers with high baseball knowledge

- Good readers with low baseball knowledge

- Poor readers with high baseball knowledge

- Poor readers with low baseball knowledge

All participants read a story about baseball (the input). They then produced the following output: (1) reenactment of the story on a board showing a baseball diamond, (2) a verbal retelling of the events of the story, and, finally, (3) a verbal summarization of the story. In each instance, participants with a lot of knowledge about baseball outperformed those without such knowledge—regardless of reading ability.

The following year, Schneider, Körkel, & Weinart (1989) looked at the effect of background knowledge on reading comprehension and recall. Participants in their study were in grades 3, 5, and 7 and were pretested to determine their overall reading ability, as well as their knowledge of soccer. Students at all three grade levels then read the same passage about soccer. The results of the study showed that at all grade levels, prior knowledge of soccer was more important than general reading ability for comprehension and recall.

Why these studies matter: None of us are good at reading everything. Students are no different. We understand more of what we read when we already have knowledge about—and are more likely to be engaged by—the topic.

Collectively, the research we’ve examined points to two important recommendations for improving English Learners’ literacy:

- Provide English Learners with more comprehensible input.

- Take advantage of English Learners’ existing background knowledge.

How digital literacy platforms support English Learners’ literacy achievement

Schools in the US and around the world are increasingly turning to digital literacy platforms—including myON by Renaissance—to provide English Learners with 24/7 access to a wide variety of engaging, authentic texts. myON offers up to 13,000 enhanced digital books—both fiction and nonfiction—from a range of respected US and international publishers. Embedded reading supports and scaffolds, including an English dictionary, professionally narrated audio, and tagging and highlighting tools, help English Learners read texts successfully, while providing educators with deep insight into their students’ engagement and progress.

English Learners use myON in the same way as native English speakers. When they first log in, they take a brief assessment to determine their current English reading level. They also complete an interest inventory to identify the topics that engage them. myON then recommends both fiction and nonfiction texts, based on each student’s reading level and interests. Students can browse recommended books before making their choice; they can also easily search the full digital library to find additional options.

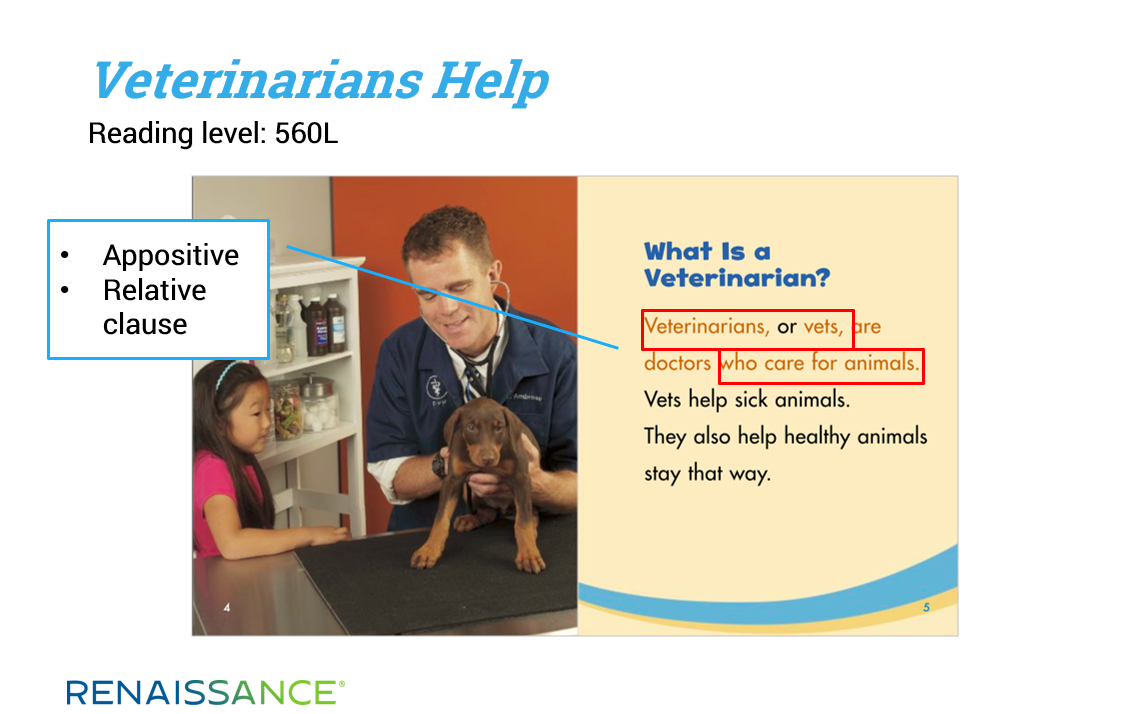

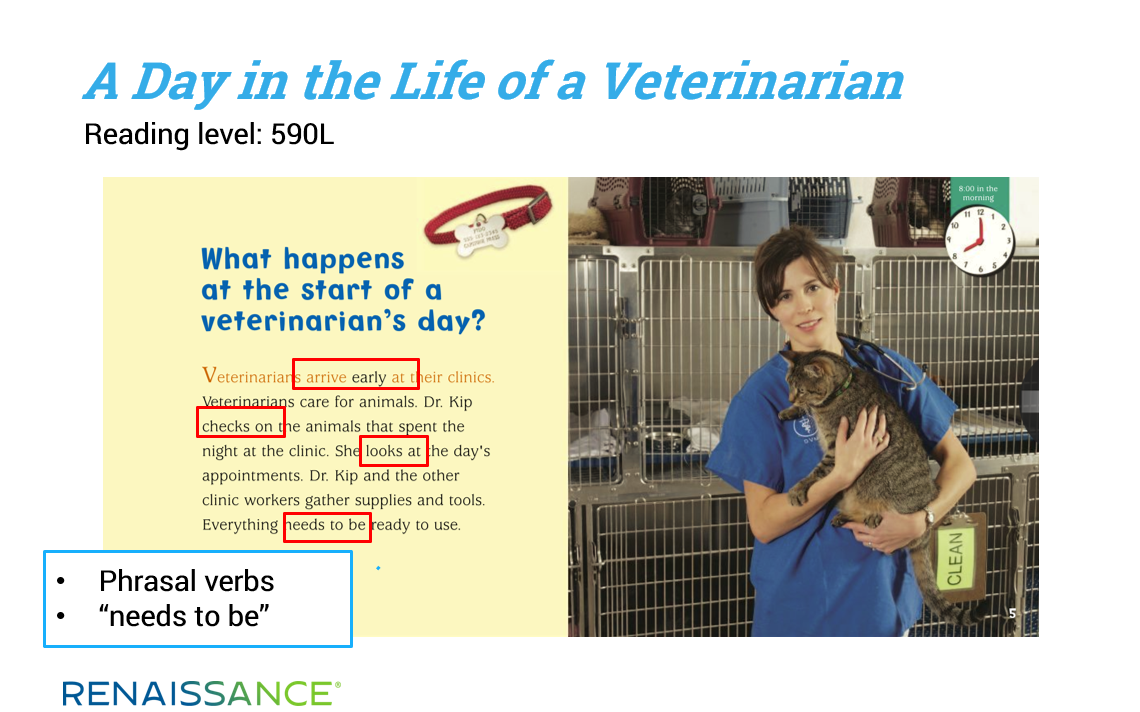

To see this process in action, let’s take the example of a hypothetical English Learner named Bella. The initial assessment shows that Bella’s English reading level—expressed on the Lexile® scale—is 590L. On the interest inventory, she notes that she’s very interested in animals. (In fact, she dreams of becoming a veterinarian!) myON therefore recommends two books to her: Veterinarians Help (reading level: 560L) and A Day in the Life of a Veterinarian (reading level: 590L).

Because these texts are at the appropriate reading level and take advantage of her existing background knowledge, they provide Bella with the comprehensible input she needs for continued literacy growth. Because these texts are authentic, they also expose Bella to language structures (appositives, relative clauses, phrasal verbs) in English, helping her to learn these structures the same way native English speakers do: through natural—and repeated—exposure.

It’s worth noting that every book in the myON library also includes professionally narrated audio to model the sounds, words, and intonation of English. This audio narration provides additional comprehensible input—at just the right level of complexity—for English Learners and supports their overall language development, in addition to supporting literacy growth.

Taken together, these features—24/7 digital access, authentic texts, a wide range of topics and reading levels, embedded supports and scaffolds, and professionally narrated audio—make a digital reading platform like myON an ideal solution for English Learners. These features also remind us how technology can support our mission as educators, which is to provide every student with the right support at the right time for success.

References

Biemiller, A. (2007). The influence of vocabulary on reading acquisition. Encyclopedia of Language and Literacy Development, 1–10.

Krashen, S. (1985). The input hypothesis: Issues and implications. New York: Longman.

Recht, D., & Leslie, L. (1988). Effect of prior knowledge on good and poor readers’ memory of text. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80(1), 16–20.

Schmitt, N., Jiang, X., & Grabe, W. (2011). The percentage of words known in a text and reading comprehension. Modern Language Journal, 95(1), 26–43.

Schneider, W., Körkel, J., & Weinert, F. (1989). Domain-specific knowledge and memory performance: A comparison of high- and low-aptitude children. Journal of Educational Psychology 81: 306–312.

Trelease, J. 2013. The read-aloud handbook. New York: Penguin.

VanPatten, B. & Williams, J. (Eds.) 2014. Theories in second language acquisition: An introduction. New York: Routledge

Learn more

Ready to see how myON will support greater literacy achievement for your English learners? Click the button below to get started.