April 23, 2021

If we’ve learned anything about surviving a pandemic, it’s that the process has more in common with a marathon than a sprint. Nothing about this was going to be over quickly. While we may have naively thought in terms of weeks when this began, we now know that the course of time necessary for both navigating and recovering from the pandemic will be measured in months and years instead. We were not ready for that message a year ago, but having negotiated things so far and with improvements on the horizon, we can now accept this.

Whether we understood it or not, it was always going to take more than a year for some control of the coronavirus outbreak to be established. This meant that it would take even longer to rebuild things both economically and academically. Last spring, multiple studies attempted to predict the academic impacts of the pandemic. Then in the fall, new studies appeared using back-to-school data to show students’ performance at the start of the school year. Now, a new crop of findings provides insight into how kids are growing this year—and whether this growth is sufficient to close COVID-related achievement gaps.

Earlier this week, Renaissance released the new Winter Edition of our How Kids Are Performing report. This new data set provides important insights on how the academic impacts of the pandemic are playing out across the country—and what steps educators can take this summer and beyond to accelerate student learning.

Addressing the academic impact of COVID-19

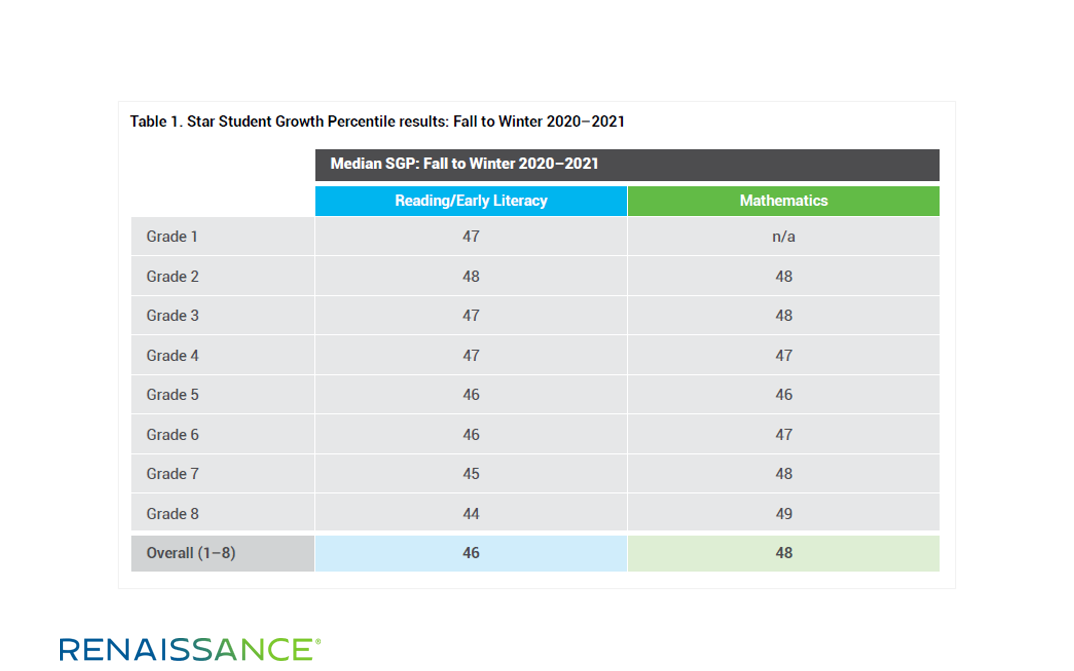

The new winter report shows that despite all of the challenges, many students are having a very legitimate school year. This is evidenced by the solid Student Growth Percentile (SGP) scores for the fall-to-winter period, drawn from our Star Assessments. While an SGP of 50 is average and these numbers fall slightly below that, the SGP scores for most grades are within a few points of 50, with the possible exception of reading in grades 7–8.

This should be considered something of a victory overall, considering the widespread concern that many students could fall further behind this school year. Such concerns were based on (a) the lack of access to in-person instruction in many places, (b) teachers not being able to fully cover content because of limited instructional time, and (c) well-founded fears about student attendance, access, and engagement in online learning.

While it’s encouraging to see fall-to-winter growth rates approaching typical levels, this also means that there is still unfinished learning from last fall. How so? Students would have needed above-typical growth rates to erase all of the COVID-19 impacts that we saw at the beginning of the school year. In reading, while students in grades 1–3 have gained ground and either remain close to expectations or are no longer behind, the average performance of students in grades 4–5 has held steady. They remain either 4 to 7 weeks behind (grade 4) or close to expectations (grade 5). Students in grades 6–8 have fallen further behind expectations since last fall, however, with those in grades 7–8 now between 8 and 11 weeks behind.

In math, where the largest drops in performance were seen in the fall, students are making headway. While students in most grades are generally now performing at a higher level than they did in the fall, these levels still vary. Students in grades 2–3 are close to expectations, while those in grades 4–8 remain behind typical-year expectations to differing degrees.

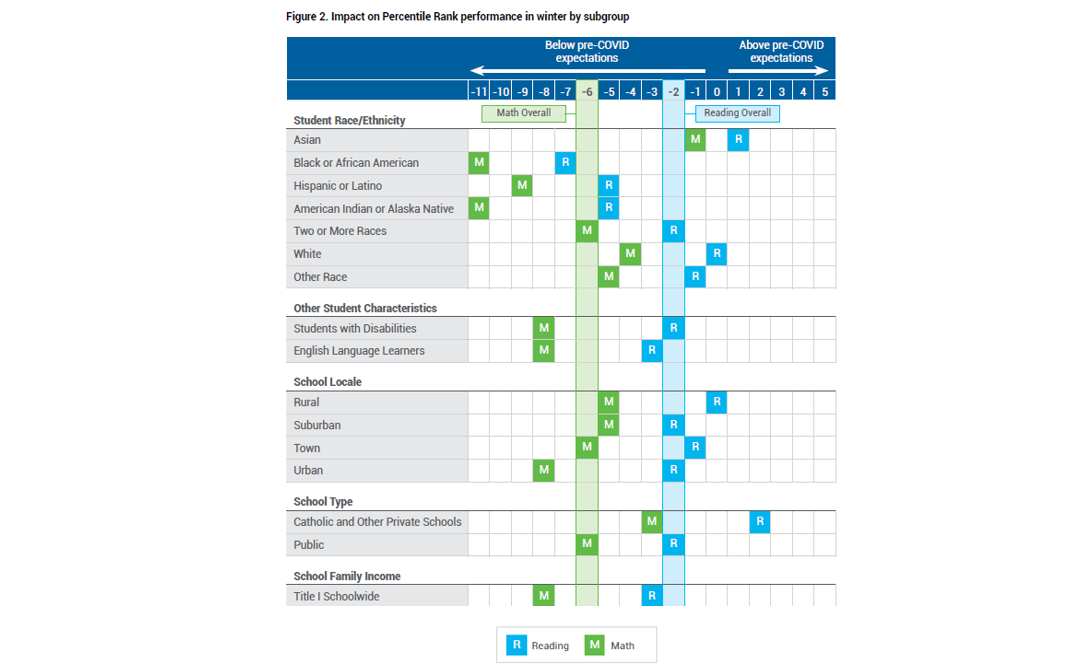

Additionally, hiding behind these high-level averages are some stark realities. Disaggregated data reveal widening gaps between demographic subgroups. In the new report, we found larger negative impacts for students who are Black, Hispanic, or American Indian or Alaska Natives, as well as students with disabilities and English Language Learners. Students attending urban schools and schools designated as Title I Schoolwide also experienced greater COVID impacts than the overall averages.

So, while there is evidence of progress, there remains both cause for concern and work to be done. The academic impacts that I have highlighted here speak not to getting students up to various benchmarks of performance, but rather to getting students back to performing at the typical or expected level in a normal, pre-pandemic school year. As we move forward, we also need to keep in mind that not only are schools faced with erasing COVID’s impact, but also with addressing the far larger gaps in achievement that existed well before the pandemic.

How one story has become multiple stories

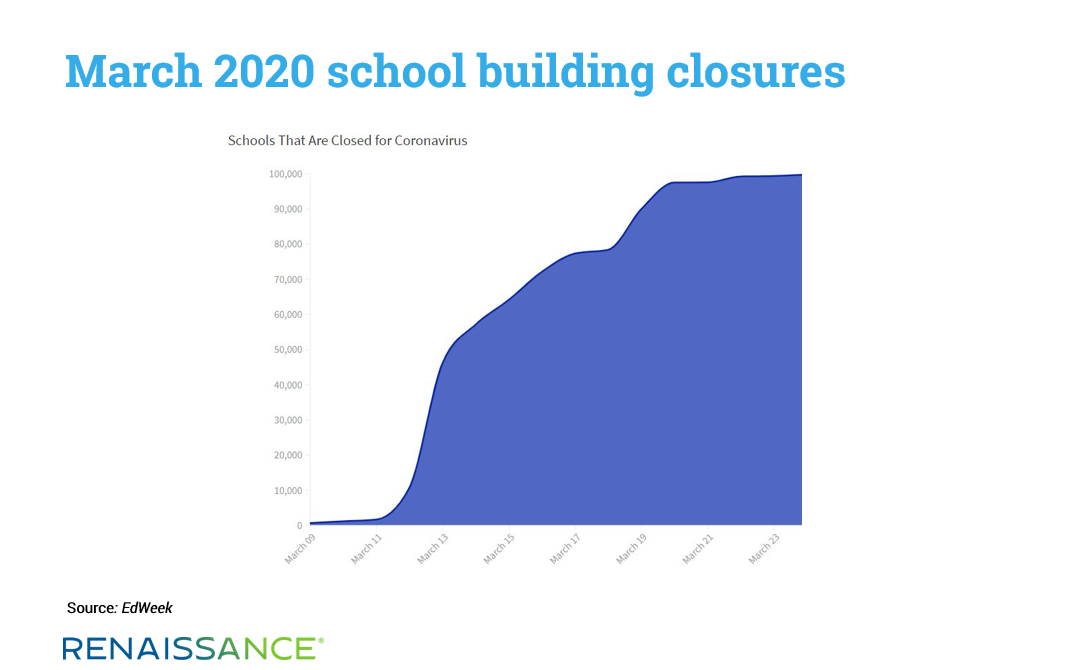

The findings in the Winter Edition of How Kids Are Performing are much harder to summarize than the findings from last fall. This is because in Spring 2020, there was primarily one story for all schools. Over a fairly short period (March 9–17), more than 75,000 schools closed their doors to in-person learning due to COVID-19. The following week, an additional 25,000 schools closed. This meant that nearly all US schools were closed, resulting in a fairly homogeneous experience for students across the nation. Whether you were in a dense urban center or the most remote, rural location, you were out of your school building.

In the fall, however, students’ educational experiences varied widely. Current estimates are that 30 percent of students are continuing with remote learning into the spring, while other students have had in-person instruction all year. Others have had every possible combination of remote, in-person, and hybrid learning experiences. Given the variety of instructional modes, is it any wonder that we see a wide variety of performance outcomes?

Focusing on students’ academic recovery

The most recent round of federal stimulus funding for education contains language and areas of emphasis that shift the focus from schools’ immediate needs to a multi-year time period for recovery. While initial COVID-19 relief bills dealt with things like personal protective equipment (PPE), reworking physical spaces, hardware, and connectivity, the recent American Rescue Plan Act addresses the need to catch students up academically through summer learning, afterschool learning, extended school days, and extended school years.

So, with the need to catch students up before us and the funding to do so provided, which approaches might prove most useful? How can we use the next 15 months of academic time (Summer 2021, the 2021–2022 school year, and Summer 2022) to address the academic impact of the pandemic? Also, what does research reveal about the most effective approaches to extended school time (extending core teaching and learning time and/or the use of targeted before- and afterschool programs) and about summer learning? And how might we adjust what we do in terms of core instruction to get greater gains from the time that we already have?

Let’s explore these areas in order of decreasing cost. Summer learning is estimated to be the most expensive approach, followed by extended day/extended year, and then by adjustments to core instruction. In this discussion, I’ll rely on the excellent research summaries done by the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) in England and presented in their Teaching and Learning Toolkit.

What do we know about effective summer learning?

Key insights regarding summer school/summer learning programs include:

- On average, summer school/summer learning experiences typically result in two additional months of growth.

- Greater impact (up to four months of growth) is possible “when summer schools are intensive, well-resourced, and involve small group [tutoring] by trained and experienced teachers.”

- “Some studies indicate that gains are greater for disadvantaged pupils, but this is not consistent.”

- “One of the greatest barriers to summer schools having [an] impact was achieving high levels of attendance.”

The EEF’s full report on summer learning is available here. When reviewing their reports, it is useful to pay particular attention to the “what should I consider” section, which highlights key considerations.

What do we know about extended teaching and learning time?

Approaches in this area include extending the school day, extending the school year, and/or providing additional learning time for targeted groups of students. Key insights include:

- On average, extended time approaches yield two additional months of growth per year. There is evidence that disadvantaged students benefit more, with close to 3 months of additional growth. This evidence also suggests “wider benefits for low-income students, such as increased attendance at school, improved behavior, and better relationships with peers.”

- Not surprisingly, programs with “a clear structure, a strong link to the curriculum, and well-qualified and well-trained staff” yield the best results.

- Programs that are less-structured and more enrichment in nature “can have an impact…but the link is not well-established.”

The EEF’s full report on extended learning time is available here. As mentioned earlier, it is helpful to pay particular attention to the “what should I consider?” section.

What’s common to both approaches?

For both summer learning and extended-time learning, the EEF stresses the power of one-to-one and small-group tutoring (which is referred to as “tuition” in England). Their guidance on one-to-one tutoring is available here.

Another consistent point is the importance of enhancing core instruction. Key elements to focus on or strategies to use in this area include (a) improvements to homework, which is shown to be most effective at the secondary level; (b) increasing the quality of feedback provided to students; (c) adopting mastery-based and collaborative learning approaches; (d) teaching meta-cognition and self-regulation strategies; and (e) providing targeted instruction on reading comprehension strategies.

A marathon, not a sprint

At Renaissance, we will continue to track students’ performance in order to better understand the differential impacts of COVID-19 by subject, grade, and demographic subgroup. We will also continue to offer free resources—such as our Focus Skills for reading and math—to help educators target the most critical learning at every grade level, both during the school year and throughout the summer. As I mentioned at the outset, the academic recovery from COVID-19 will require years rather than weeks and will be closer to a marathon than a sprint. But every journey begins with a single step—and a clear view of the road ahead.

Download the new Winter Edition of How Kids Are Performing for more insights on students’ recovery from COVID-19. Also, learn more about the report—including a discussion of remote vs. in-person test administration—in our new on-demand webinar. To watch, click the button below.